Navigating Platinum (PGMs)

Scientific Properties of Platinum (and other PGMs)

Platinum group metals (PGMs) include platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd), rhodium (Rh), iridium (Ir), ruthenium (Ru) and osmium (Os). These metals have extremely unique scientific properties such as high densities of 21.45g/cm³ and very high melting points of 1768°C. PGMs also have corrosion resistance and exhibit excellent resistance to oxidation, even at high temperatures. For this reason, platinum has also been a relatively understudied metal given that it was difficult to refine and work with pre-industrialization. Platinum also possesses good electrical conductivity which is vital for various electronic applications. PGMs are also chemically stable and inert, which contributes to their durability and longevity in various applications.

Uses and Future Applications

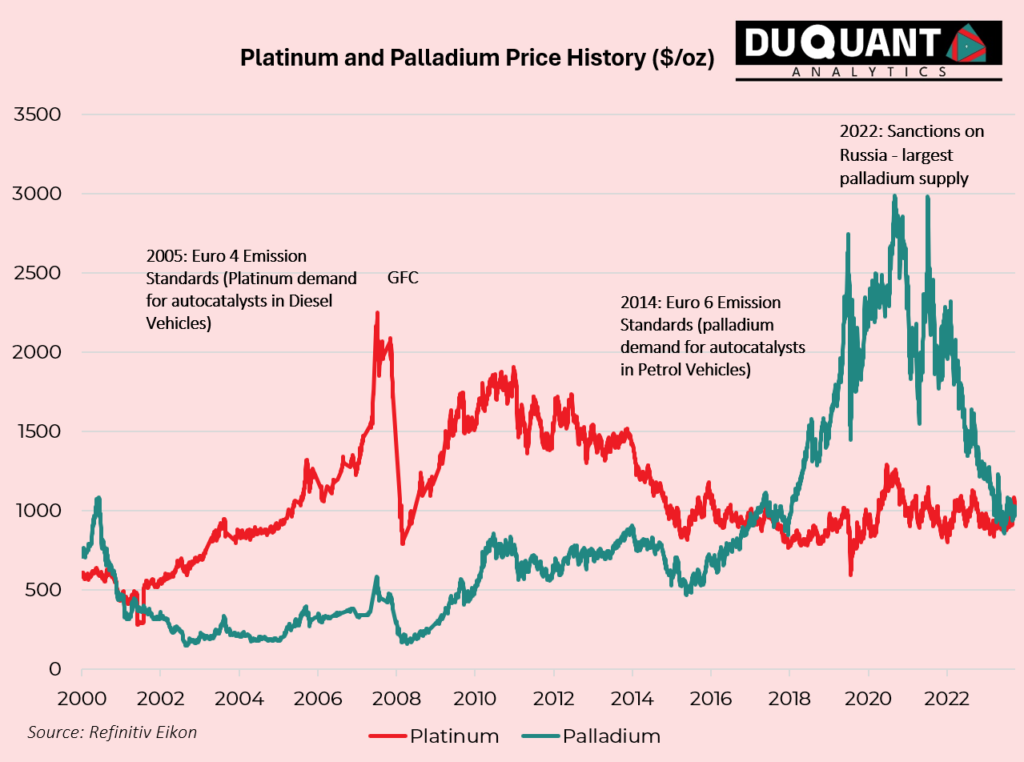

Given the non-corrosive properties of platinum, durability and aesthetics appeal, it has become a highly demanded material used in jewelry, as well as an investment as a precious metal similar to gold and silver. PGMs are also critical components in catalytic converters in automobiles, which reduces harmful emissions from internal combustion engines (ICE). The early 2000s platinum boom, as well as the late 2010s palladium boom was largely driven by the introduction of the UN’s Euro emission standards (4 to 6) which placed regulations on all vehicle emissions and required petroleum and diesel vehicles to make use of autocatalysts which reduce CO2 emissions. These catalytic converters contain PGMs as a critical component, given the durability and heat resistance, an thus this drove much of the demand in the last 2 decades. Platinum is also used in various industrial applications such as chemical manufacturing, electronics and glassmaking. With a high melting point and durability at high temperatures glass can be poured and set into PGM based molds.

Future facing sustainable applications of these remarkable metals are vast, with applications in hydrogen fuel, catalytic converters, electromechanical implants, the production of fertilizers, fiberglass, surgical instruments, and even cancer treatments. Platinum’s future use in the green hydrogen space is still highly speculative with much debate among investors and science. Platinum group metals are used in electrolyzers for splitting water molecules to produce hydrogen gas, which is considered a clean fuel, – but at the moment around 30% of the energy put into hydrogen production in this form is lost, and requires more research to improve efficiency. The potential for an energy transition to a hydrogen economy is that hydrogen is the most abundant element and our oceans are full of it, and thus to make use of it for energy would be ground breaking. PGMs are essential for hydrogen fuel cells, which are used for converting hydrogen back into electricity while emitting only water as the byproduct which is perfect for vehicles. Platinum is said to be an ideal material to be used as a proton exchange membrane (PEM) in fuel cells and is even said to be a more suitable fuel cell for electric vehicles than traditional batteries. This is due to the rapid startup time and low operating temperatures. Koji Sato, the executive chairman of Toyota said, “Our new hydrogen engine will destroy the whole EV industry.” The potential is huge, however, the practicality of rolling out a hydrogen economy comes with its own challenges and will be discussed in future newsletters as it could play a role in shaping the future. Hurdles to overcome are the distribution and conversion efficiency in hydrogen production.

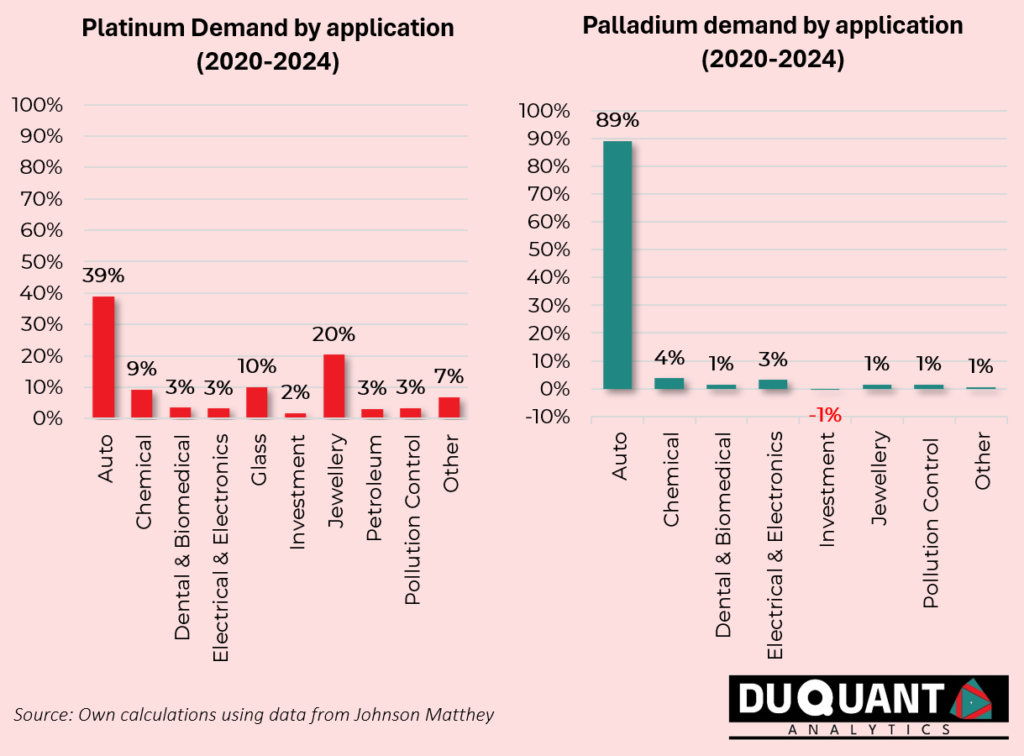

In terms of global PGM demand as determined by Johnson Matthey, 2024 demand for palladium is 9.731 Moz, 7.614 Moz for platinum, 1.167 Moz for Rhodium, 1.105 Moz for Ruthenium and 0.237 for Iridium. Thus, making Palladium and Platinum the most demanded PGMs. The figure below shows a summary of platinum and palladium demand by application.

An important thing to note is that while palladium demand is greater than platinum, palladium demand is much more concentrated to the automobile industry (particularly autocatalysts in petrol-based combustion engines). From this point of view as the world transitions away from combustion vehicles, the demand for palladium is at greater risk than platinum which has much more diversified sources of demand. Palladium is also less demanded by investors and jewelry makers as noted by the decline in investment demand over 2020 to 2024 and only 1% of palladium demand is in jewelry (compared to platinum at 20%).

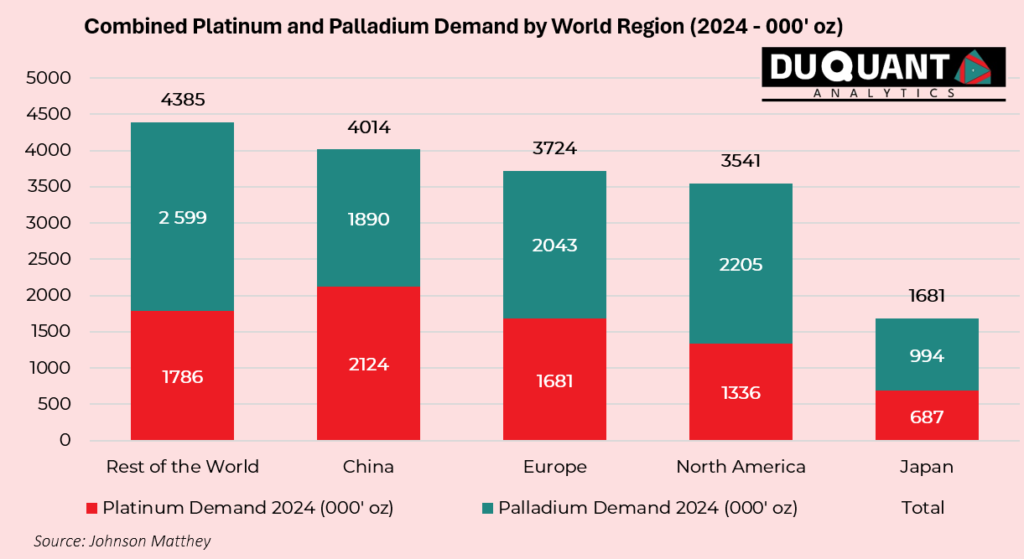

In terms of countries that demand PGMs, China is the largest, followed by Europe, North America and Japan. A key thing to note is that over the decade 2010-2020 according to the South African Revenue Service (SARS) customs export data from South Africa, c.25% of PGM exports were destined to Japan, thus making Japan a key role player in the PGM metals exchange. Japan seems to be a middle man exchange player given that a large portion of China’s PGM buying takes place with Japan, – even though Japan has no platinum mines themselves. China also sources majority of its palladium from Russia. Japan and China are key markets for PGMs given their scale and volume of automotive manufacturing.

Largest Sources and Producers of Platinum and Palladium

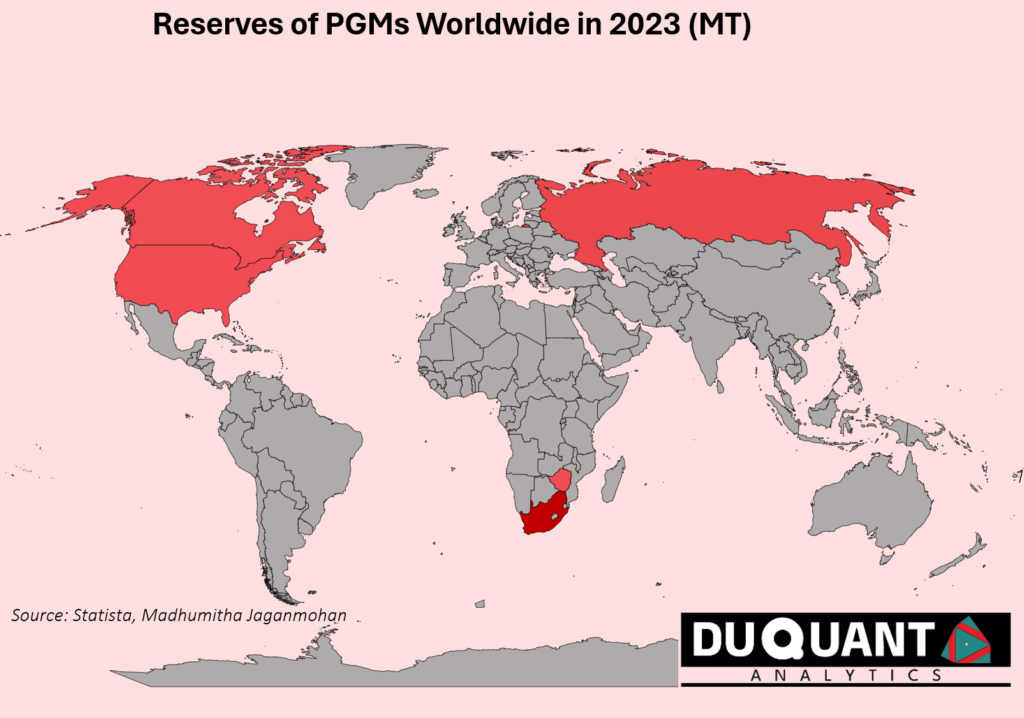

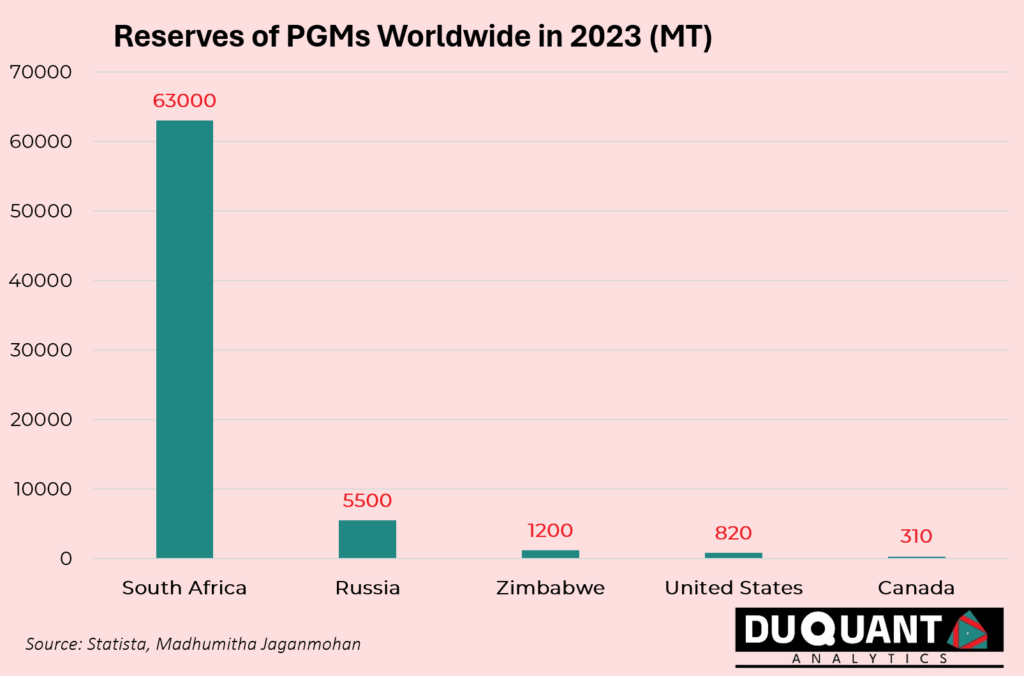

PGMs, which include platinum, palladium, rhodium, iridium, osmium, and ruthenium, are found in regions such as South Africa, Russia, USA, Canada, and Zimbabwe. To visualize how rare these metals are, imagine that all the gold mined in the world would fill up 4 Olympic swimming pools, while the amount of platinum would fill one Olympic swimming pool to the height of your ankle. Thus, PGM’s are far scarcer than gold, and the supply of these metals is also highly concentrated to a few regions globally, with the Bushveld Complex in South Africa being the most significant platinum resource ever discovered, followed by Russia, Zimbabwe and Canada. These regions (apart from Canada) are also regarded as politically unstable. Thus the upside case for PGMs as a precious metal investment would be due to its importance as an industrial metal, physical scarcity, coupled with supply side constraints.

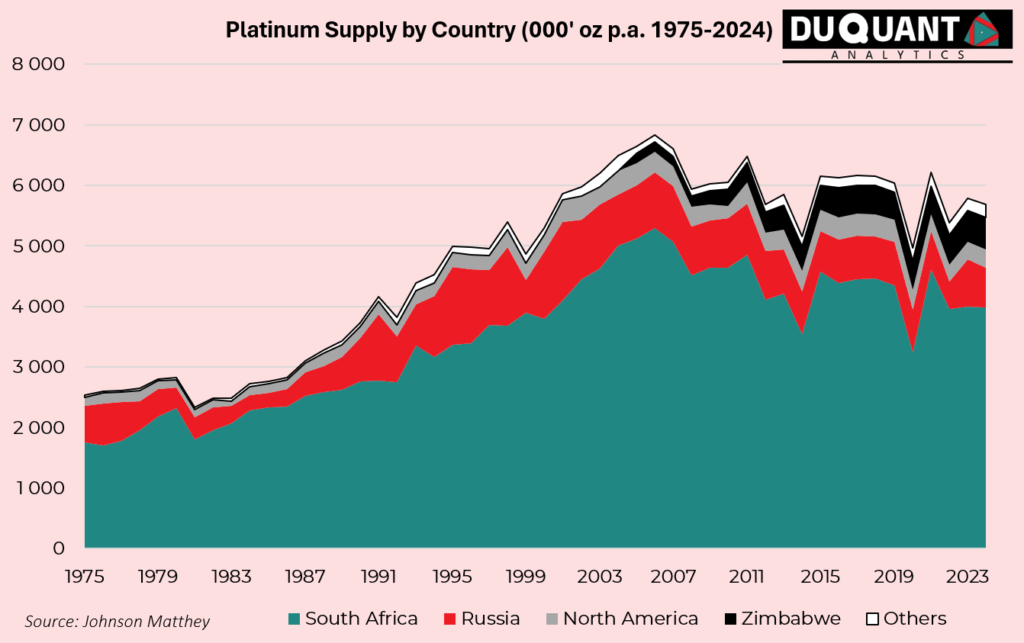

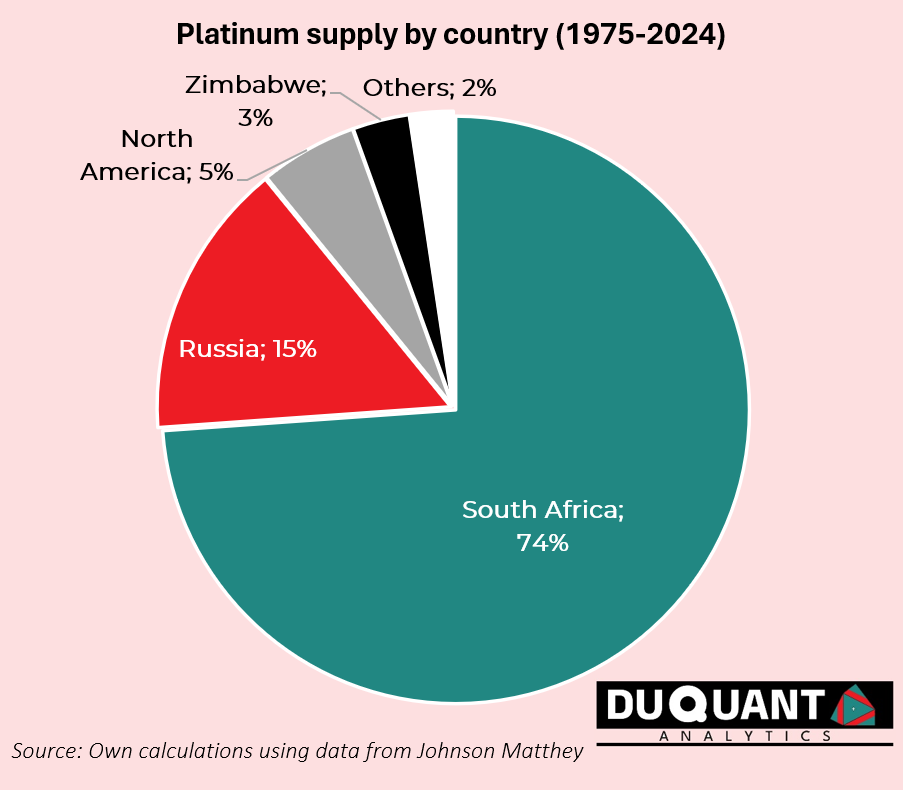

Both platinum and palladium are significant in their industrial use, and use in autocatalysts that play a role in reducing carbon emission in internal combustion engine (ICE) automobiles. South Africa is the largest producer/supplier of platinum making up c.74% of global platinum supply, followed by Russia, the second largest producer making up 15% of platinum supply since 1975. The third and fourth largest regions are North America and Zimbabwe contributing 5% and 3% respectively, while the rest of the world is insignificant making up only 2% of supply. These statistics highlight the concentration risk underlying the supply of platinum, especially when considering that South Africa continues to grapple with rolling blackouts, a stagnating economy and declining road and rail infrastructure, and Russia remains sanctioned by the west.

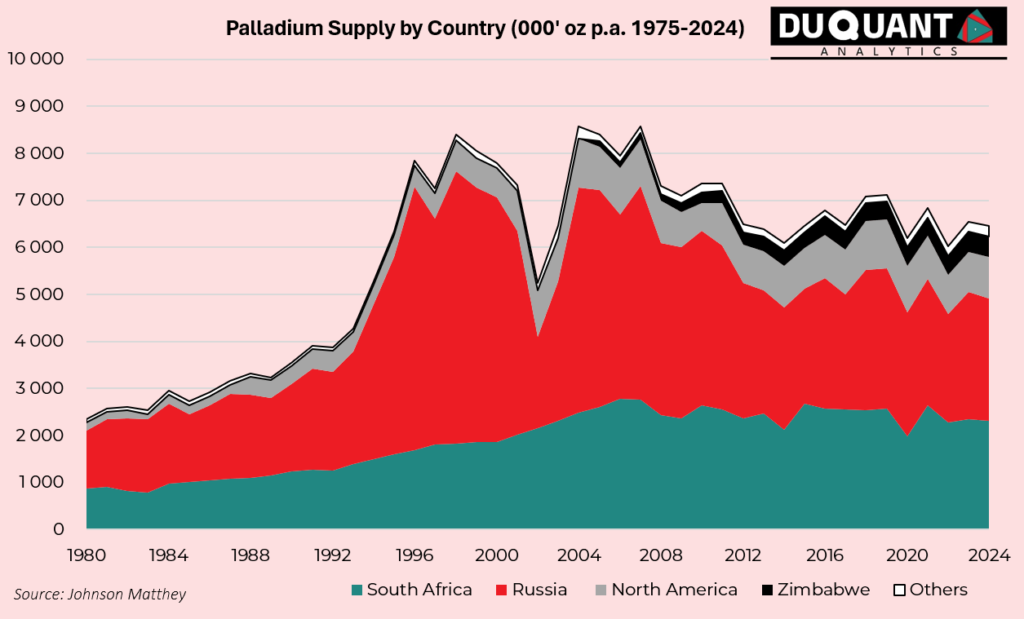

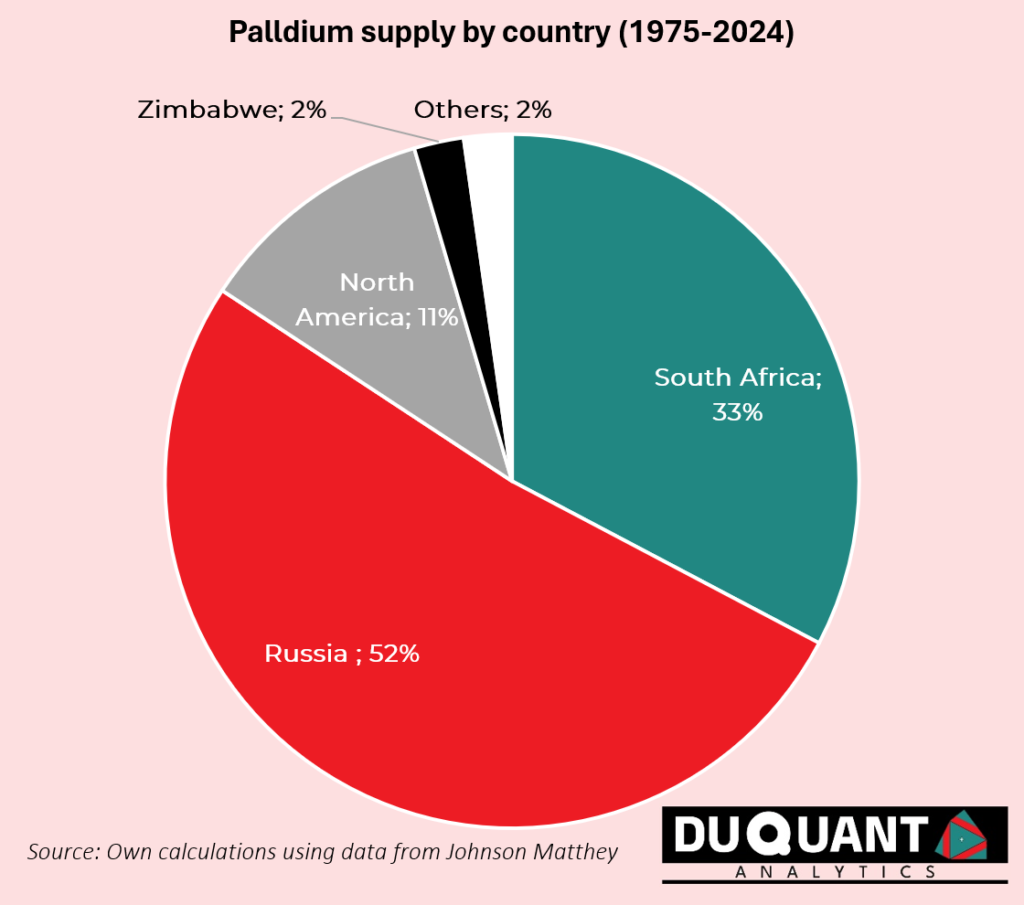

In the case of palladium, the supply is slightly different as Russia makes up 52% of palladium supply since 1975, followed by South Africa which contributed 33% of palladium supply. The differences in platinum and palladium contributions have largely to do with the differences in PGM basket grades/mixes in the South African Bushveld Complex vs the Russian Norilsk-Talnakh mining district in Siberia. South Africa holds more platinum as opposed to palladium, while Russia’s deposits are among the world’s largest sources of palladium. An interesting dynamic to note is that palladium mining in Russia is actually a byproduct of nickel and copper mining what this means is that the more nickel and copper that Russia mines, the more palladium they produce as a byproduct. This dynamic coupled with the fact that palladium demand is 89% driven by automobiles, there might be a future risk of oversupply with declining demand as the world adopts EV’s. Investors should thus be more cautious with palladium than in the case of platinum.

The Remarkable History of Platinum (and other PGMs)

Platinum and other platinum group metals (PGMs) have played a significant role throughout history and continue to play a vital role today. The story of platinum is a tale of remarkable discoveries and transformative impacts. The journey began with ancient civilizations of South America, where pre-Columbian cultures unknowingly used platinum for decorative purposes. However, it wasn’t until the 18th century that platinum captured European attention. In 1735, Spanish explorer Antonio de Ulloa first documented platinum in the rivers of Colombia, describing it as a mysterious and unworkable metal (given its high melting point it was not easy to form and refine). Meanwhile, in 1748, British scientist Charles Wood brought attention to platinum’s unique properties after his research. While conducting experiments with gold and silver Charles found a peculiar white metal that resisted heat and did not dissolve in any of the acids known at the time, and this resistance to corrosion and toughness differentiate platinum from other metals.

Fast forward to the early 20th century, and the scene shifts to South Africa. In 1924, geologist Hans Merensky discovered the most significant platinum deposits ever found. This is formally known as the Bushveld Igneous Complex, a large region spanning 4 provinces in South Africa and teeming with platinum deposits near the surface. This discovery revolutionized the global supply of PGMs, propelling South Africa to the forefront of the platinum mining industry. The vast deposits in the Bushveld Complex, located in the Limpopo, North West, and Mpumalanga provinces, transformed not just the local economy but the entire global platinum market. To this day the correlation between the South African Rand and the platinum price also suggest that the Rand is a platinum backed currency to a large extent.

The mid-20th century saw another leap forward with the invention of catalytic converters in the 1970s. PGMs, particularly platinum, palladium, and rhodium, became essential in reducing harmful vehicle emissions, catalyzing cleaner air standards worldwide. The automotive industry’s reliance on these metals highlighted their environmental significance and cemented their place in modern technology and transportation. The excitement continues into the 21st century as PGMs pave the way for a sustainable future. With the growing focus on green technologies, platinum is now at the heart of hydrogen fuel cells, and could be key in powering the next generation of clean energy vehicles. In regions like the Waterberg and Northern Limb of South Africa’s Bushveld Complex, ongoing explorations promise even more discoveries, ensuring that PGMs remain at the cutting edge of technological advancements.

Examples of investment opportunities where the sector benefited from decreasing carbon emissions was the 2019 palladium boom, largely driven by European Euro emissions policies that saw an increase in autocatalysts regulation and demand for palladium use in petrol vehicles. This palladium boom was beneficial to investors as well as the Russian and South African economies. South African miners such as Impala Platinum saw huge profits out of palladium which was mostly a byproduct in the production of platinum itself. Since the Ukraine War in 2022 and US imposed sanctions on Russia, some speculation has been that Russia is supplying palladium off market which is leading to depressed PGM spot prices globally as less on market volumes are traded over the counter (OTC). Another explanation for the weakening prices of these metals is due to tighter monetary conditions, less economic activity out of China due to CV19, and a global shift into EV’s, thus a large chunk of PGM demand in autocatalysts is put into question.

From ancient jewelry to modern clean energy, the history of platinum and its sister metals is a saga of continuous innovation and global impact. This historically understudied metal (given its high melting point) could have many more undiscovered use cases that could be uncovered.

Longer term prospects for PGMs beyond combustion vehicles are looking favorable given the unique properties of the metals, their use in industries and potential use in a green hydrogen economy, as well as their store of value as precious metals relative to that of gold and silver. As we look to the future, PGMs could be set to drive the next wave of breakthroughs in energy and technology, proving that their story is far from over, and for an investor could be a great opportunity of a lifetime.

More posts on Platinum Group Metals:

Navigating Platinum (and other PGMs)

Navigating Platinum (and other PGMs) What makes these rare and resilient precious metals shine in…