Navigating Oil

Scientific Properties of Oil

Oil is a complex mixture of hydrocarbons, which are organic molecules made up of carbon (C) and hydrogen (H) atoms and extracted from underground reservoirs. It varies in composition, is greasy and tends to be liquid at room temperature (depending on properties such as density, viscosity, and sulfur content influencing its quality and uses). Oil is primarily found in sedimentary rocks (shale – a organic material containing rock formed from mud/clay and hardened under immense pressure over a long time) and is extracted through various drilling techniques. It is used as a fuel for transportation (e.g., gasoline, diesel), heating, and electricity generation. Oil also serves as a feedstock for petrochemical products such as plastics, lubricants, and synthetic fibres.

Uses and Future Applications

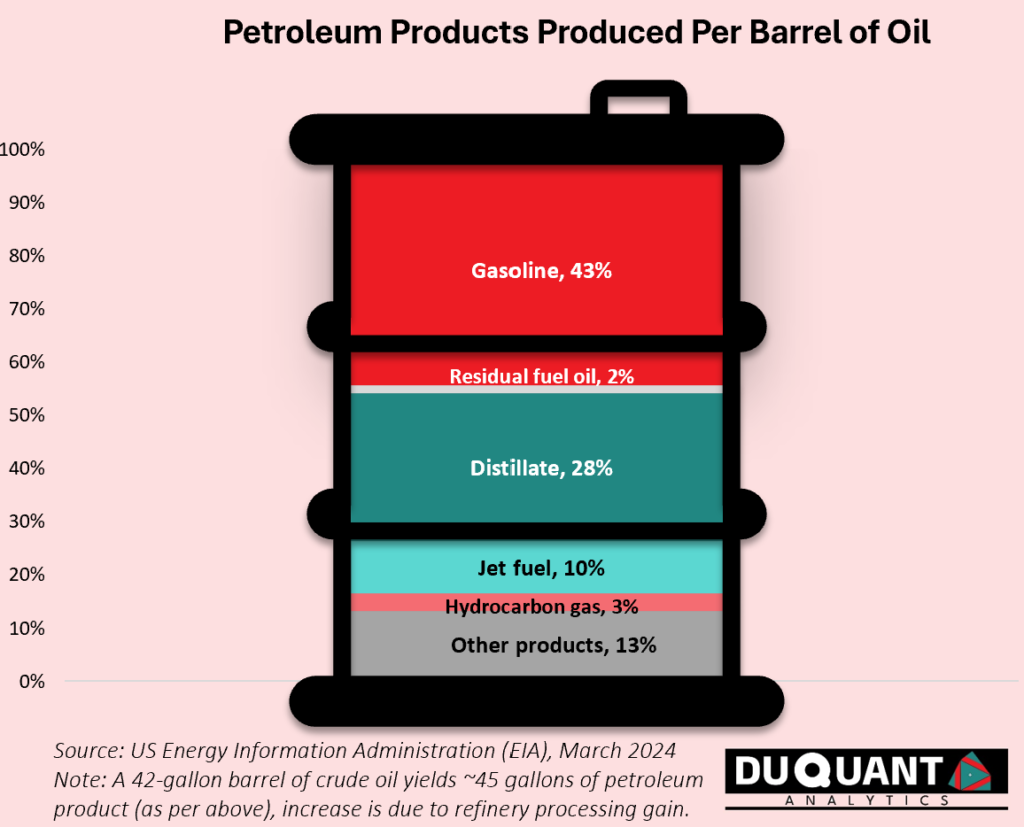

Oil, or petroleum, is a versatile resource with numerous applications across industries. Its primary use is in transportation, where it powers vehicles through gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. Industrially, oil serves as a raw material for plastics, synthetic fibers, rubber, and lubricants, as well as asphalt for road construction and roofing. It is also critical for electricity generation in oil-fired power plants and heating through residential and commercial heating oil. In agriculture, petroleum-based fertilizers and pesticides play a key role in crop production. Additionally, oil is used in consumer goods like cosmetics, detergents, and medical supplies, and it supports military operations by fuelling jets, tanks, and other vehicles. The primary uses of oil can be visualised as per below by observing the end use of a 42-gallon barrel of oil:

Globally, the largest oil importers are countries with high energy demands but insufficient domestic production. China leads as the world’s biggest importer, driven by rapid industrialization and urbanization. The United States, despite being a significant producer, imports oil to meet its vast consumption and refinery needs. India follows closely due to its growing transportation and industrial sectors. Japan and South Korea, with limited natural resources, rely heavily on imports for energy and industrial purposes. In Europe, countries like Germany, Italy, and France are key importers, while Singapore acts as a major refining and trade hub. Other significant importers include Indonesia and Thailand, reflecting the critical role of oil in supporting industrial and consumer energy demands worldwide.

Largest Sources and Producers of Oil

Over the past century, oil production has evolved significantly, driven by technological advancements and growing global demand. In the early 20th century, production was characterized by conventional drilling techniques, focusing on large, easily accessible reservoirs. Regions such as Texas, the Middle East, and Russia emerged as dominant producers due to abundant reserves. By mid-century, innovations like offshore drilling expanded exploration to underwater fields, further boosting supply. Over time, enhanced recovery techniques, including water and gas injection, improved the extraction efficiency of mature fields. Despite these advancements, traditional oil production remained geographically concentrated, reinforcing the power of oil-exporting nations and shaping geopolitics through organizations like OPEC.

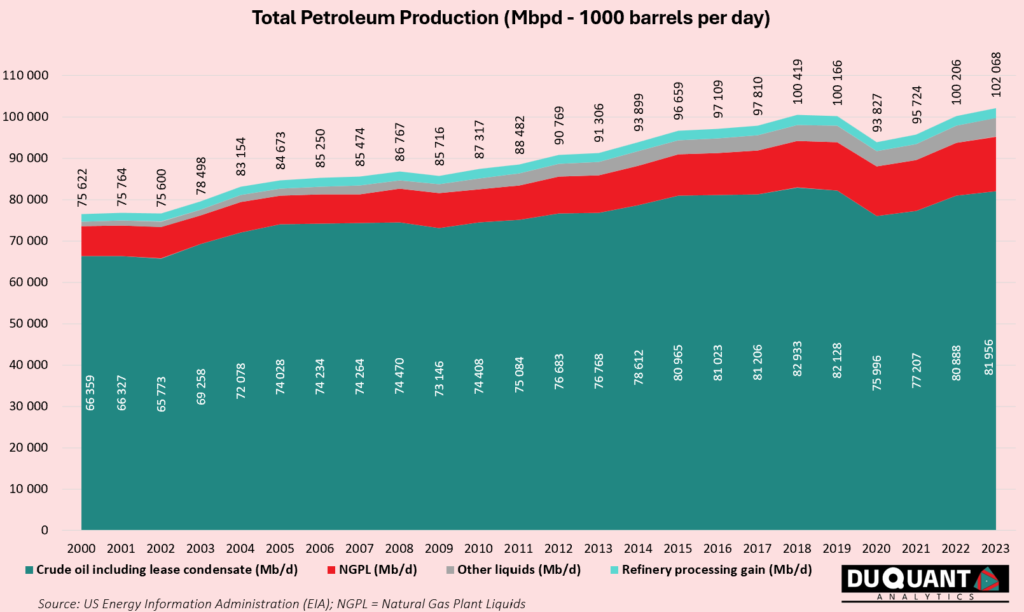

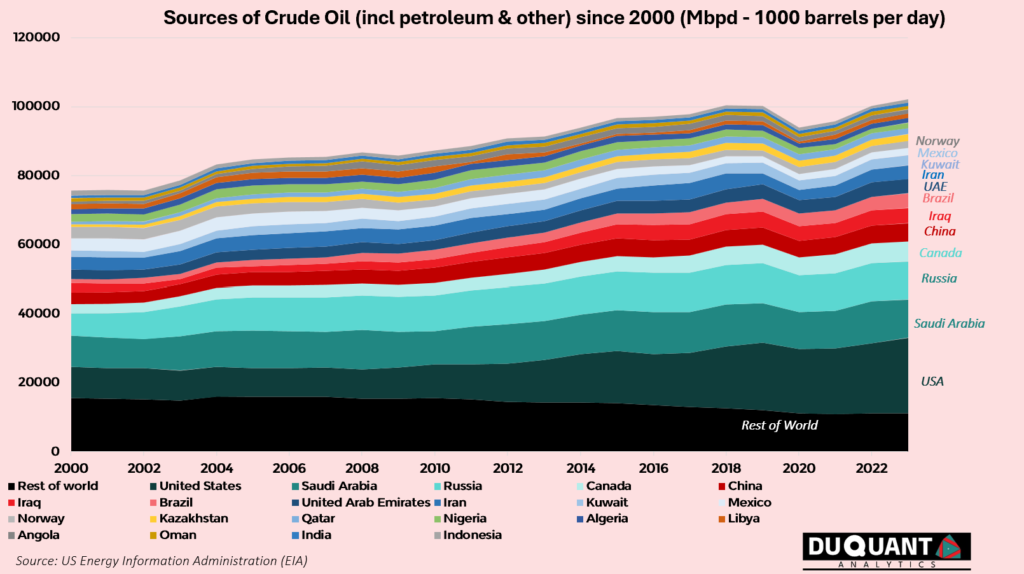

Oil production techniques have undergone remarkable evolution, driven by technological advances and growing energy demands. Initially, oil was extracted through vertical drilling, targeting large, shallow reservoirs that were relatively easy to access. Early oil fields relied on rudimentary rigs and manual labour. The introduction of pumpjacks, commonly known as “nodding donkeys,” revolutionized the industry by enabling continuous extraction from wells with declining natural pressure. These iconic machines became symbols of conventional oil production, particularly across Texas and the Middle East. Over time, offshore drilling extended oil exploration to deepwater reserves, while enhanced recovery techniques like water flooding and gas injection improved extraction efficiency. By the late 20th century, the industry was employing advanced seismic imaging and directional drilling, laying the groundwork for even more transformative innovations. All the advancements in oil extraction methods meant that global oil production has increased at a CAGR of around 1.37% per year since the year 2000.

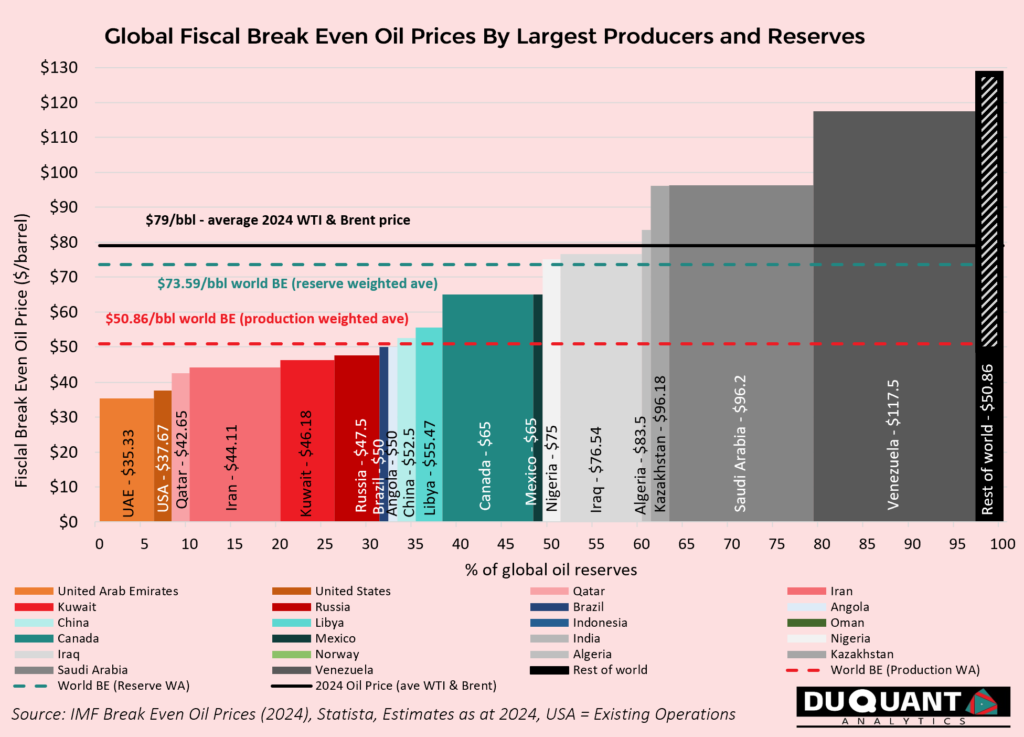

The US shale revolution represented a turning point in oil production and global energy dynamics. Key innovations in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling allowed producers to unlock oil trapped in shale formations, previously considered uneconomical. Unlike conventional methods, horizontal drilling enabled operators to drill laterally across vast shale layers, significantly increasing the surface area exposed to fracking. High-pressure water, sand, and chemicals were then used to fracture the rock, releasing oil and gas. This method, pioneered in the United States, dramatically boosted domestic production, particularly in regions like the Permian Basin and Bakken Formation. This technology transformed the U.S. into the world’s largest oil producer, challenging traditional market leaders like OPEC and Russia. This method of extraction also meant the number of above ground rigs could decline significantly as the yield and coverage per rig increased rapidly. Shale’s responsiveness to price fluctuations, due to its short production cycles, has created a range-bound oil market where prices typically hover between $40 and $80 per barrel. Lower prices curb shale production, setting a price floor, while higher prices incentivize rapid output, capping price spikes. This flexibility has not only reshaped the market but also diminished the geopolitical leverage of oil-rich nations in the middle east, heralding a new era of energy independence for the U.S. and greater volatility for traditional powers.

The shale revolution marked a seismic shift in global oil dynamics. Beginning in the early 2000s, breakthroughs in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling unlocked vast reserves of shale oil in the United States and transformed the U.S. into the world’s largest lower-cost oil producer that could compete with traditional powers like OPEC by introducing significant new supply at a competitive price.

Globally, the estimated break-even price of oil is $51/bbl (2023 production weighted average), and thus, this level sets a natural floor in the oil price (a price below which a majority of the worlds oil producers begin to be unsustainable). Based on using the reserve weighted averages, the fiscal break-even price is around $74/bbl, which could be viewed as a more longer-term floor price as reserves enter into extraction phases. Thereby, using these estimates it could be expected that oil should trade above $51/bbl (or $74/bbl over the medium-long term) in order for the supply of oil to remain stable. These figures are also subject to change based on new oil discoveries and technological breakthroughs.

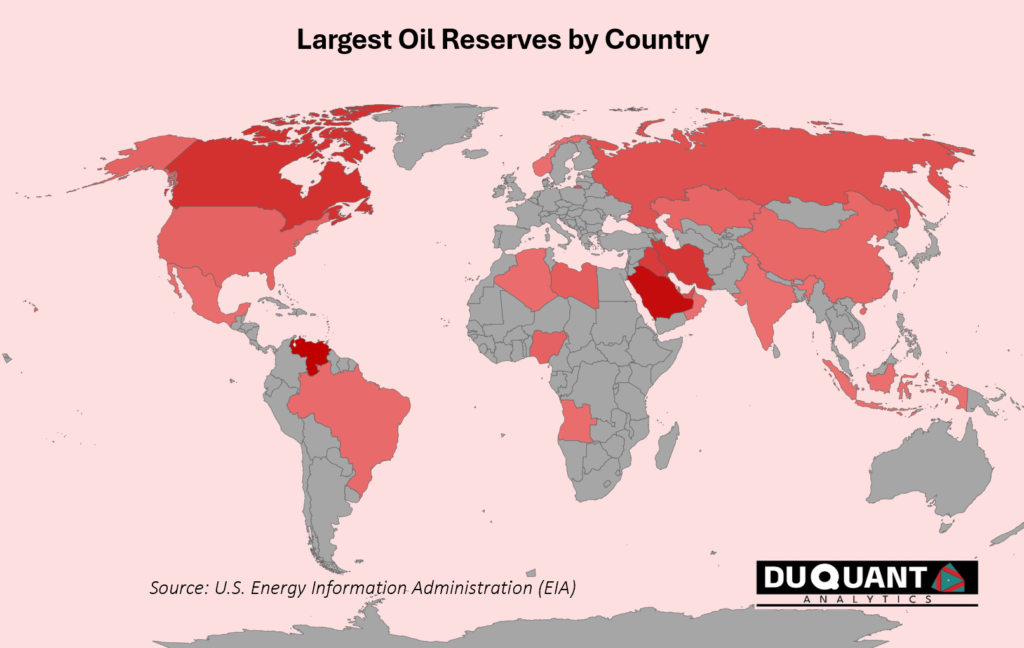

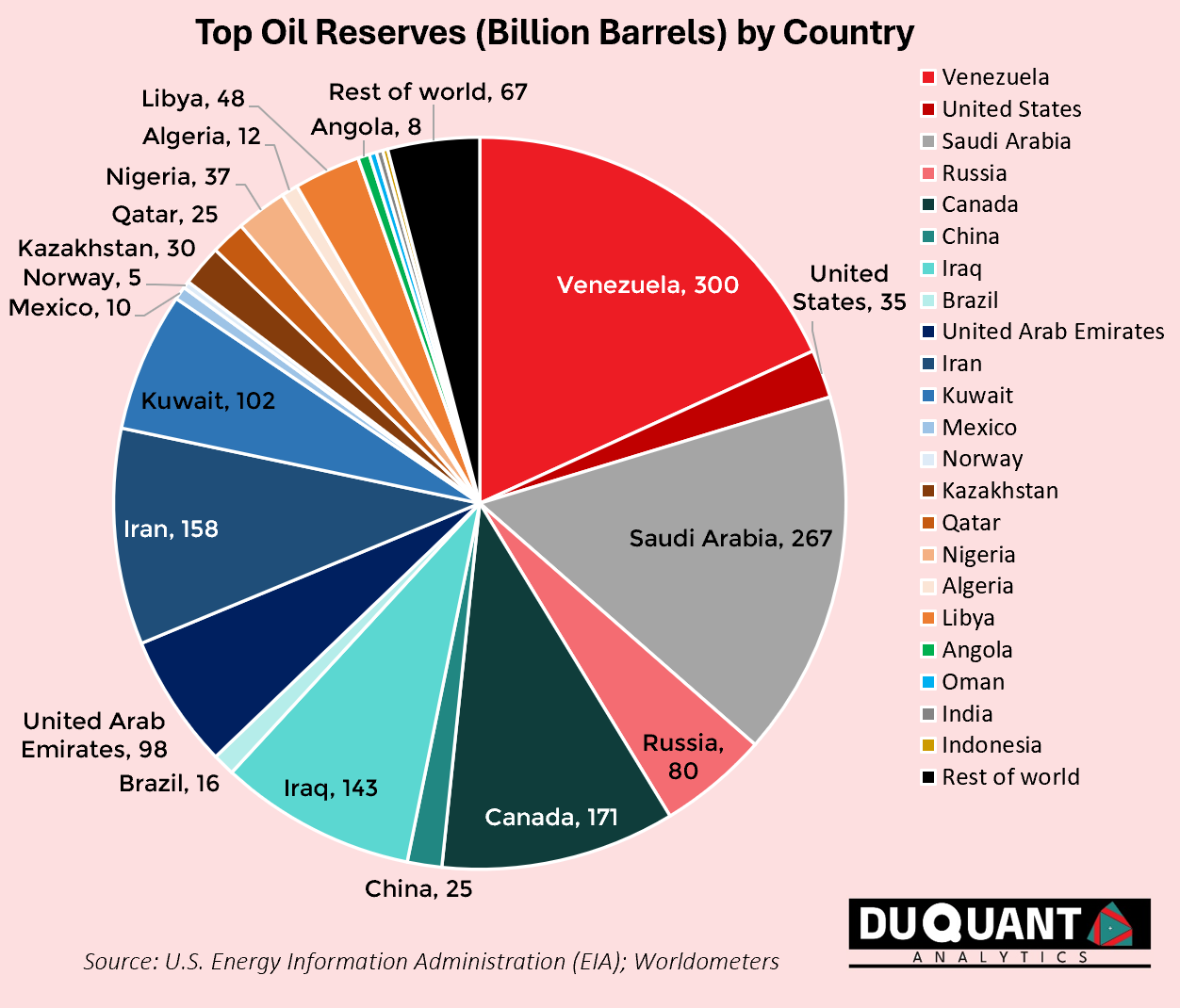

Venezuela has the largest known oil reserves in the world (18.2% of global), however, oil production has sharply declined due to mismanagement, lack of investment, and economic instability, compounded by U.S. sanctions imposed in 2017, which targeted its oil sector and restricted access to international markets.

Saudi Arabia has the second largest oil reserves (16.2% of global) and has been a strategic ally of USA since the establishment of the Saudi petrodollar deal in the 1970s, where Saudi Arabia agreed to price its oil exclusively in U.S. dollars in exchange for military protection and political support from the United States. This deal, formalized in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, effectively linked global oil markets to the U.S. dollar, creating a steady demand for the currency. This arrangement helped strengthen the U.S. dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency, as countries worldwide needed dollars to purchase oil. The petrodollar system has continued to shape global finance and trade, ensuring that the U.S. dollar remains dominant in global markets, however, in more recent years this dynamic has been shifting when Saudi Arabia agreed to start selling oil in Chinese yuan in 2022 – part of a broader effort to deepen economic ties with China, who is naturally a large trading partner and the world’s biggest importer of oil.

Canada has the worlds third largest oil reserves (~10% of global), primarily concentrated in the oil sands of Alberta. These reserves consist largely of bitumen, a thick, heavy form of crude oil that requires specialized extraction methods. Canadian oil sands operations are energy-intensive and more costly compared to conventional oil extraction, like light sweet crude oil in large accessible reservoirs in the Middle East, or shale oil field in USA. These factors make Canadian oil more costly, carbon intensive, and sensitive to price fluctuations.

The next largest oil reserves are in the Middle East, including Iran (9.5% of global), followed by Iraq (8.7%), Kuwait (6.1%) and UAE (5.9%). Russia is the 8th largest making up 4,8% of global reserves, and ideally located to supply Europe.

According to the the US Energy Information Administration, (EIA), roughly 102 million barrels of oil (including petroleum & other) were produced per day in 2023. Over the last two decades (since 2000), 14% of all oil & petroleum production came from USA, followed by Saudi Arabia (~12%), Russia (~11%), China (~4.9%), Canada (~4.5%), Iran (~4,4%), UAE (~3.7%) and Iraq (~3.5%). The rest of the world accounted for roughly ~41%.

Based on current reserves of oil (1650 billion barrels) and current consumption of oil (~97 million barrels per day), the world has roughly 47 years of oil supply remaining. Thereby highlighting the further importance of transitioning the global energy mix away from fossil fuels out of the need to sustain the global economy and living standards, which are currently extremely abundant compared to pre-1900s living standards.

The Remarkable History of Oil

Oil has played a pivotal role in shaping modern human civilization, economies, and geopolitics. Oil’s history dates back thousands of years, with early Middle Eastern civilizations recognizing its natural occurrence and diverse applications. In ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), bitumen – a viscous form of petroleum – was used as early as 4000 BCE for waterproofing boats and as mortar in construction. This marked the first known use of oil-based products in human civilization. The uses pre-19th century was small-scale and limited.

In the 1850s, the world’s first commercial oil well was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, USA, by Edwin Drake. This event sparked the modern petroleum industry, as oil began to replace whale oil and coal as the primary source of energy for lighting and heating. Oil also has a major advantage over coal as it can be pumped and poured, making transportation and refuelling much more efficient than coal. John D. Rockefeller’s establishment of Standard Oil in the 1870s revolutionized the oil industry through vertical integration and aggressive business tactics. Standard Oil became the world’s largest oil refiner and distributor, dominating the global oil market. The discovery of the Spindletop oil field in Texas in 1901 ushered in the era of large-scale oil production in the United States. This discovery led to a surge in oil exploration and production, propelling the United States to become the world’s leading oil producer.

Oil had initially focused on producing kerosene for lighting in oil lamps, but with the advent of electric lighting that started to become common place in the early 1900s, kerosene’s importance started to decline. Henry Ford then entered the picture and revolutionised the automobile industry by introducing the Model T in 1908 and pioneering the assembly line production method in 1913. This innovation in automobile manufacturing drastically reduced the costs of automobiles, making them affordable for the average consumer. Ford’s advancements transformed cars from luxury items for the wealthy into essential tools for everyday life. The widespread adoption of automobiles following Ford’s breakthroughs significantly increased the demand for oil, particularly gasoline, which became the primary fuel for internal combustion engines and benefited oil refiners. This boom in demand boosted oil’s role within the economy. Ford’s impact accelerated the transition of oil into a cornerstone of modern industrial economies, reshaping energy markets, transportation, and driving the development of global oil infrastructure. This trend spread across the world and the automobile market grew rapidly, particularly in Europe (1920s-1930s: Citroen, Fiat & Volkswagen) and in Japan (1930s-1950s: Toyota & Nissan).

During the interwar period (WWI & WWII), significant oil discoveries were made in the Middle East, particularly in countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Iran. These discoveries transformed the region into a global hub for oil production and export, laying the foundation for modern oil geopolitics. The mid-20th century witnessed unprecedented global demand for oil, driven by economic growth, industrialization, and technological advancements. Oil played a crucial role in World War II, fuelling military operations and industrial production. In the post-war period, oil became synonymous with economic development and modernization, powering automobiles, airplanes, and manufacturing industries worldwide.

The formation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in the 1960s and the oil crises of the 1970s reshaped global oil dynamics. OPEC’s collective action to control oil prices and production levels exerted significant influence over global energy markets and geopolitical relations. The 1978 oil crisis, stemming from the Iranian Revolution, significantly disrupted global oil markets and contributed to widespread inflation. The overthrow of the Shah and ensuing political turmoil in Iran (a major oil exporter that still accounted for ~4.4% of supply over the last two decades) resulted in a sharp drop in oil production, creating fears of supply shortages. These anxieties were exacerbated by panic buying and OPEC raising prices, which nearly doubled oil prices by 1979. This surge in energy costs rippled through economies worldwide, increasing production costs and triggering inflation, particularly in developed nations dependent on imported oil. The crisis underscored vulnerabilities in global energy security and contributed to stagflation – a combination of stagnant growth and rising prices – forcing governments to explore alternative energy sources and adopt conservation measures.

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed fluctuating oil prices, driven by geopolitical tensions, economic recessions, and technological innovations in oil exploration and production. Advances in offshore drilling and extraction techniques expanded global oil reserves and production capacities.

Growing concerns over climate change and environmental sustainability prompted efforts to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, including oil. The rise of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency initiatives challenged oil’s dominance in the global energy mix. The 21st century presents oil with new challenges and opportunities amidst shifting global energy landscapes. The debate over peak oil -whether global oil production would reach its maximum capacity and decline – intensified in the early 2000s. The shale revolution, driven by hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technology, unlocked vast reserves of shale oil and gas in the United States, reshaping global energy markets.

The adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 underscored global commitments to mitigate climate change and transition towards low-carbon economies. The agreement signalled a pivotal moment for renewable energy development and reducing fossil fuel dependency, including oil. Post Paris Agreement and into the 2020s, sentiment has been focused on the accelerating energy transition towards cleaner and more sustainable alternatives to oil. Governments, industries, and consumers are increasingly focused on reducing carbon emissions and promoting renewable energy sources, challenging the long-term outlook for oil demand. This is particularly a focus given the substantial impact that carbon tax initiative could have on carbon emitting countries and industries – potential making many of them unfeasibly when pricing carbon taxes into the equation.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted global oil markets, leading to a sharp decline in oil demand and prices whereby oil futures went negative for the first time in known history, and there was no enough storage space to accommodate the production of oil at the time. This crisis highlighted oil’s vulnerability to external shocks and accelerated discussions on resilience, diversification, and sustainability in energy systems. Coming out of the pandemic, in March 2022 the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, and sanctions imposed on Russia led to a sharp increase in oil prices, – particularly given that Russia has made up ~11% of global production of oil over the last two decades. This lead to Brent Crude oil prices going up to $126/bbl in March 2022 (compared to ranges of $60/bbl to $80/bbl over the last 5 years).

Looking ahead, oil faces a dual challenge of meeting global energy demand while addressing environmental sustainability and climate goals which place a major question mark around growth in the oil market. Technological innovations, regulatory frameworks, and competing market dynamics will shape oil’s future role in a transitioning global energy landscape. Efforts to decarbonize oil production, improve energy efficiency, and integrate renewable energy sources will be crucial in defining oil’s resilience and sustainability in the coming decades.

Oil’s journey—from ancient bitumen to modern petroleum—reflects humanity’s quest for energy, progress, and prosperity. As the world navigates complex energy challenges and transitions towards a more sustainable future, oil remains integral to global economies and lifestyles. The evolution of oil continues to unfold, driven by innovation, geopolitical dynamics, and societal aspirations for a cleaner and more resilient energy future.

Navigating Oil

Navigating Oil How has oil revolutionized the modern world, and where does this “black gold”…